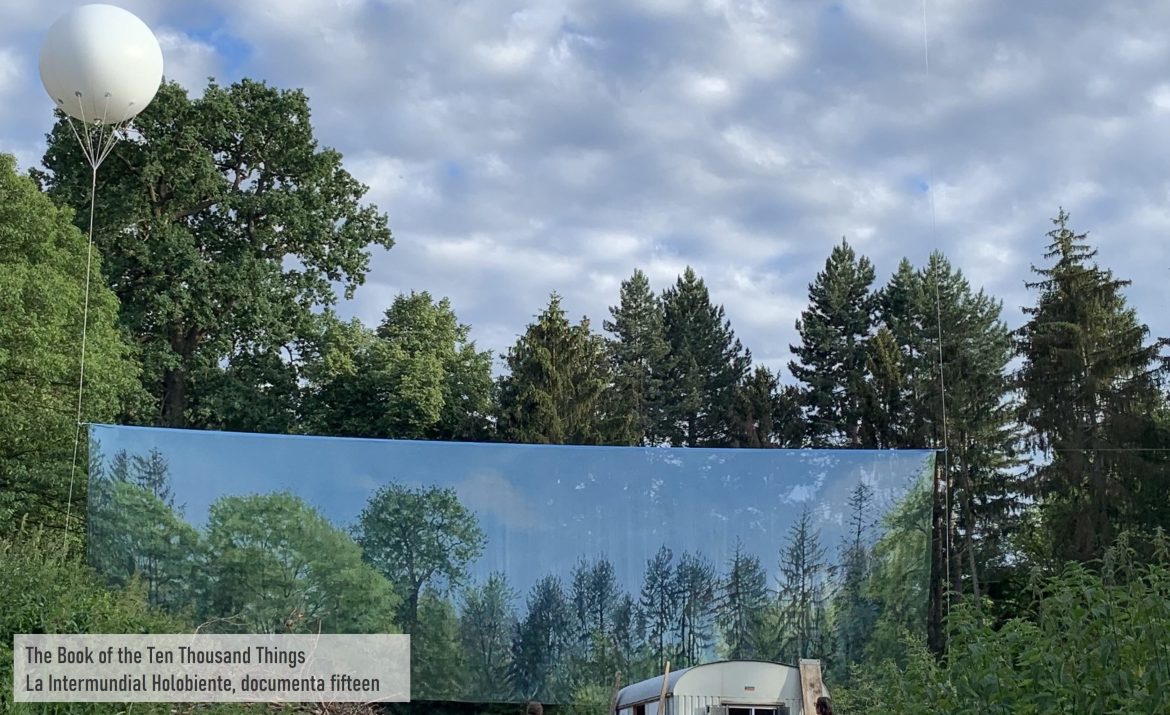

Finally, it came to the end of the long exhibition of documenta Kassel 15. Walking through more than 30 venues all over the city, it has been a long journey of Byvision delivering the onsite report on documenta, which has almost nothing to do with works of art as “objects”, but instead focuses on continuity and on-site creation.

At the 59th Venice Biennale it was already shown to us: in art all the signs point to upheaval. At documenta fifteen it becomes even more obvious. Art, as we know it from the art market, from galleries, museums and auction houses, is increasingly slipping into the side program – which can be seen particularly well in Venice: the blue-chip artists from Georg Baselitz to Anselm Kiefer are in magnificent with their paintings and sculptures Palazzi spread across the city, presented by their galleries and far from the official Biennale program. In the country pavilions, on the other hand, a new era is beginning. For the first time, more indigenous people can be seen as the focus than ever before. Their contributions are usually more closely linked to their thematic concerns than to our art-historically developed ideas of quality. In the Philippines pavilion, handicrafts are repositioned when the weaving technique is upgraded: the sound of the looms is translated into patterns for meter-long lengths of fabric. In some other pavilions, the focus is on imparting knowledge, for example when the Selk’nam tribe in the Chile pavilion share their concern for Moore with an elaborate video installation. They see the swamp as a living body that needs to be protected as a valuable ecosystem – rightly so, because only 3 percent of the earth’s surface is covered by wetlands, which seal around 500 gigatonnes of carbon.

For audiences who have experienced a long epidemic, the social atmosphere of Documenta has provided relief from years of isolation fatigue. This ruangrupa exhibition is obviously different from most biennales familiar to the public. This is not a list of works that can be examined. The exhibition is more about the sharing of methods, the gathering of archives and the embrace of various experiments. Although it seems to be against the art market, for many art audiences who come and go in a hurry, facing these “works” that require time and communication costs to control the leopard, it seems that they can only watch others play while hesitating whether this is also the case. A form of the current experience economy.

Ruangrupa’s conceptual framework for the exhibition is “lumbung”, which means “rice granary” in Indonesian, a public granary managed collectively in the village for emergencies; another important Indonesian word is “nongkrong”, It refers to everyone getting together to hang out and blow water. Under the guidance of these two conceptual tools, a lively art scene centered on shared resources and sustainable creation seems to be a logical realization. ruangrupa has invited a total of 67 core groups, many of whom have years of practical experience, and most of them are from outside the commercial art circle and the global south. Through a decentralized approach to curation, ruangrupa gives groups full freedom and confidence to develop their creative and organizational talents.